I'm out of breath for two reasons. First, I stayed up until 2 AM dancing at the big party at the annual American Astronomical Society (AAS) meeting. Picture eight hundred sweaty, grinning, goofy scientists bouncing around in a variety of tempos on a packed dance floor. It's so awkwardly goofy and charming there aren't words. This may sound corny, but the AAS dance party gives me hope that we are building a better profession, where we want our scientists to make amazing discoveries -- and be happy.

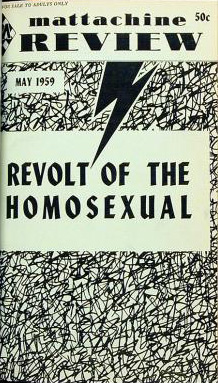

But what really takes my breath away is how quickly the situation is changing regarding the inclusion and acceptance of lesbian, gay, and bi scientists in my profession.

When I attended my first AAS, I was a deep-in-denial undergrad, sublimating my confused passion into problem sets. In my heart I knew I wasn't straight, but I hadn't realized I could be a lesbian. I didn't know any gay people, except for one poetry professor (heart). I knew it was possible, though really hard, to be a successful woman scientist, but I didn't think there were any gay scientists. All this sounds so unbelievably quaint now, the foghorn of the Titanic may Blwwoooorn any minute.

After I came out in grad school, someone invited me to the AAS LGBT networking dinner. We were to meet at the registration desk at an appointed hour. Many of the crowd were regulars -- we just celebrated the 20th anniversary of this dinner! But for a newcomer it seemed really closed and closety. Were we ashamed? Did we need to be afraid of being noticed? I scanned the crowd. "Um, are you guys going to, um, the dinner?" Blank stares, wrong group. Once I found the right group and walked to dinner, it was wonderful. I met a scientist whose partner was also in academia. Their institution recruited them as a two-body hire, and they had domestic partner benefits! I was at a queer-unfriendly university at the time, so this story sounded like unicorns on roller-skates to me.

That networking dinner was a lifeline. We bitched about some of the hurtful comments we'd gotten, we sympathized about the difficulty of living apart from partners because we couldn't find jobs together, or couldn't get visas. We dished about which institutions were "tolerant", and which were hostile. We bragged about what famous astronomers at our institutions were okay with us being gay. We lamented that many of the activists for women in astronomy wanted us to go away, because lesbians weren't "real women" in science -- we were an unsympathetic distraction from their goal of enabling the straight woman scientist to raise a wholesome nuclear family. We also laughed an awful lot, told jokes, mentored, listened, shared. I don't remember talking much, but I remember inhaling it all. Here were grad students, postdocs, planetarium and observatory staff, and actual faculty members who were gay and succeeding in science.

In math, an existence proof isn't a general solution, but one that demonstrates that the problem is solvable. That LGBT networking dinner was my existence proof. Yes, I could integrate the two intense, simultaneous metamorphoses of my life in graduate school: becoming a real astronomer, and falling deeply love with a woman -- into a whole person, the new me. An AstroDyke.

This year, for the first time the AAS meeting included an LGBT reception. It was announced in the conference program, and advertised by bulletin board and business cards. The turnout was at least 80 at any one time, a happy buzzing crowd, enjoying and building community. It was the Coming Out party for LGBT inclusion and diversity in astronomy. Queer students, postdocs, and faculty members attended, as did department heads and the president of the AAS. Even a few people whom I feel weren't very helpful in the past, were there proudly showing their support now. Folks sipped wine (sponsored by a defense contractor, sigh), and talked about how to build a more inclusive profession. Then the queers went off to a fabulous networking dinner, marveling at how times have changed.

The next morning I wandered around the poster hall, wondering if I'd dreamed it all. Did most of the places where I'd applied to be a postdoc really not have domestic partner benefits? Was it really true that my advisor, an otherwise great mentor, told me he couldn't help queer couples solve the two body problem, because they weren't married and who knew how long such relationships would last? Is it really true that my first interaction with the director of my postdoctoral institution had to be asking for them to add DP benefits, so that my partner would have health insurance when she moved to be with me? (They did, to their credit.)

At dinner following a recent colloquium I gave, a postdoc asked, politely, why we as a profession should worry about LGBT inclusion in astronomy, when the problems of women and minorities are much harder. He was really surprised by my response, that in my own career, it's been much harder to be a gay person in science than a woman in science. He had no idea.

That's changing. At this year's dinner, one of the undergrads, when I asked what the AAS should be doing to promote LGBT inclusion, apologized -- he had nothing to add, because he had no negative experiences being gay and a science major. "Good," I said. "I want that to be true your whole career." We're not there yet, not nearly yet. We're still a profession that favors straight white men. It's still much harder to be black, or queer, or a parent.

But it's getting better. The students at the AAS this year included a gentleman with a foot-long spiky pink mohawk, a young man in a kilt, tons of women, including ones with skirts and nebula-print tights. I saw quite a bit of blue hair, and a few men leading their young children through the exhibit hall. I was encouraged to meet African-American, Native American, and Latino students, though their numbers are still far too small. We are slowly becoming the profession I want us to be.

We are still not an inclusive profession when it comes to LGBT issues. There are still significant legal as well as policy barriers that trip up the careers of LGBT scientists, and we still sadly encounter unsupportive, even hostile workplace climates. This stuff's gotta change. Over the next year, WGLE, the AAS's Working Group for LGBT Equality, will make a roadmap for how astronomy departments can support LGBT inclusion and remove discriminatory practices in their workplace. If you care about these issues, please join WGLE (1-2 emails per month). Just send an email to wgle@aas.org.

Oh, and the last wonderful thing is that at the last two AAS meetings, I met a few other queer women to dance with. G-rated stuff, mind you. Just goofily grooving to the music, finding community, gaining strength to go back to our own institutions, be our fabulous selves, and succeed in science.